PLAY

If last year we called for a PAUSE, to stop and slow down, in this edition of Getxophoto we are encouraging you to do the opposite and press another button: this year, let’s hit PLAY.

But what does this mean? As well as being the most popular key on all our devices, the one we use to play images, music and all types of audio-visuals, play refers principally to the idea of starting up. It evokes stimulation and movement, impulse and liveliness. Just as we press play for our favourite songs, we press play in ourselves when we get going, when our spirits rise. And it is this idea of activation – pressing the button of life – that best corresponds to the original meaning of the word. Because to play is probably the most creative human occupation that exists.

Games are central to the history of humanity. However, for a long time they were considered an unimportant activity, a kind of back garden of culture; they have been confined to the world of childhood or identified only with toys. Nevertheless, playing is a complex activity that appears under different guises. Sports and competitions are games, as are betting and games of chance, and of course, all forms of entertainment, from video games to the performing arts because, in many languages, playing also means acting a part or playing an instrument.

Therefore, offering a single definition of playing is almost impossible. Some games impose many rules while others give way to the realm of total freedom; some are individual and others collective; some are pure fun and others are extremely serious. What is clear is that playing is a higher-order human practice, basic in learning, present in all areas of life and inseparable from the arts. When we say play, therefore, we refer to that immense universe of activations and, in particular, their impact on the imagination.

THE SACRED CIRCLE

If we look at the images that come to mind when we think about a game, they probably all have something in common; there is almost always an area marked out on the ground, a parallel world outside of reality, a social act governed by different rules or, in general, a state of exception separated from the ordinary course of things. Games, according to those who study them, are rather like a sacred circle, a space-time of a ritual nature that activates a community of the faithful around it. A football game is a ceremony, in the same way as a play that takes place on a stage. Just like a card game or a sack race. Just like a costume party or a video game session. All of these situations take place in specific environments, subject to their own laws.

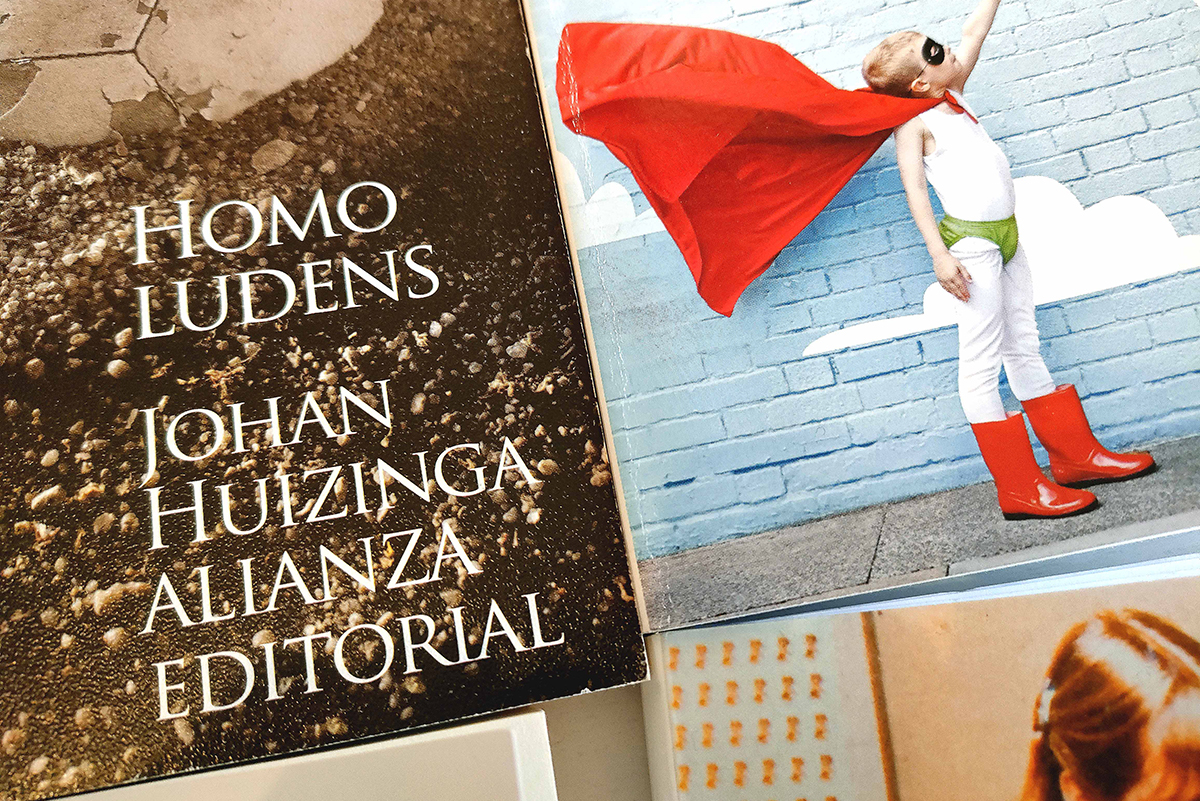

The first to notice this ritual dimension of the game was a Dutch historian called Johan Huizinga who, in the 1930s, launched the provocative idea that human beings are not special because of our intelligence (homo sapiens) or for the manufacture of tools (homo faber), but because of our obsession with playing. In his essay Homo ludens (1938), he states that all important manifestations of culture –in all civilizations– have a component of play. From playing comes liturgy, poetry, philosophy, legal institutions and even war.

This sacred origin, linked to the transcendent construction of the community, is found in many games that survive to this day. In pre-Columbian America, the ball tournament represented a fight for mastery of the stars where the sphere –the ball– was the equivalent of the sun. In the East, kites symbolised the souls of the deceased, connected in imagination to the earth and given over to the movement of air currents. In ancient Egypt, the tombs of the pharaohs included draughtboards on which, under the auspices of Osiris, the deceased gambled on eternal life. According to Huizinga, playing has a symbolic function that synthesises and sublimates a social purpose. When staging an action, we are trying to influence the order of the cosmos and bring on an event. Rooted in ritual, play changes the world.

The next stage in the recognition of play as a cultural object worthy of study came with Donald W. Winnicott, a British paediatrician and psychoanalyst, and the author of the theory of the “transitional object.” This is Winnicott’s term for the object that helps the baby separate from the mother’s breast and recognise itself as independent. This object can be anything, although it almost always takes the form of a toy, but what is important is the transition phenomenon that accompanies it. Play, says Winnicott, is an early form of thinking. When they play, the child understands the difference between themselves and the outside world; they experiment with perception and develop a creative connection with the world. “Only in play can the individual be creative and only by being creative does the individual discover the self”.

FROM COMPETITION TO VERTIGO

Due to its link with creativity, playing is naturally linked to artistic practices. But its impact on the field of culture, and particularly on the area of images and visual culture, moved to another level with the explosion of the leisure and entertainment industries in the 20 th century. It is no coincidence that the most fruitful theory about play comes from a member of an avant-garde artistic movement: the sociologist and surrealist Roger Caillois. In Games and Men (1958), Caillois proposes four categories or gateways to the diversity of the ludic experience: competition (referred to using the Greek term agôn), chance (alea), simulation (mimicry) and vertigo (ilinx). More than half a century later, these categories are still valid for understanding contemporary games, from mass sporting events to online multiplayer video games.

Sports and all games of rivalry belong to the first category (agôn). No matter whether skill, strength or memory is being measured, the goal is to defeat the opponent, assert superiority and bring home the victory, in the form of a trophy or prestige. For this reason, competitions are great ceremonies of collective identity. Winning is also the object of the second category (alea), which corresponds to games of chance, although, in this case, the result does not depend so much on skill as on luck. Although there is some room for manoeuvre in cards, in dice, bingo or roulette the player is passive and has to accept their good or bad fortune. However, this lack of action is made up for by adrenaline. The stimulus is not winning but rather the risk and its spectacular derivative: the presence of danger.

The third category (mimicry) coincides with entertainment activities since it contains all the arts governed by the muses: theatre, poetry and music. In Germanic languages and also in many Romance languages, playing means interpreting, whether it is the character of Hamlet, the rhymes of a sonnet or the chords of a song on the guitar. Playing is entering the magical world of the show and the masquerade, of fiction and simulation. The fourth category, finally, refers to vertigo (ilinx) characteristic of the most memorable amusements of childhood –rolling down a grassy slope, shooting down a slide– and of many forms of adult play linked to the loss of control. Amusement parks, popular festivals and, of course, arcade games belong to this category marked by frenzy, agitation, speed or even madness. Here the game is like a Dionysian force, a vortex –the literal meaning of the Greek word ilinx– that perfectly encapsulates contemporary visual overabundance, because if there is anything that defines the present, it is the uncontrolled, dizzying relationship we have with images.

However, of all the current expressions of games, the one with the greatest impact on the visual field is undoubtedly video games. Even surrounded by endless stereotypes – that they are popular, that they are technological, that people who don’t play them don’t understand them – they are nevertheless the most emblematic cultural expression of the 21st century, the one that has invented a form of unprecedented experience. In the video game, the ludic drive that runs through the history of civilization is united with the technological extension characteristic of the contemporary subject, which is computer code. The sacred circle, the essence of the game in all its variants, is reactivated and translated into a new regime of images whose potential we are just beginning to glimpse.

These approaches to the idea of the game are here in this edition of Getxophoto. Some projects approach it as a theme, always open to new readings, while others are designed as a playful proposal in themselves, an invitation to play with and through images. But all of them are based on the conviction that playing is a relevant phenomenon, worthy of attention, which brings us together, interrogates and explains us, which never stops changing and surprising us, and through which we portray ourselves as a society.

In Getxophoto 2024 you will find proposals that, from the field of image and photography, explore games and playing from these points of view and from many others that have not occurred to us.

Shall we play?

REFERENCES

Donald W. Winnicott, Realidad y juego, Gedisa, 1987

Roger Caillois, Teoría de los juegos, Seix Barral, 1958

Mathieu Triclot, Philosophie des jeux vidéo, La Découverte, 2017

Johan Huizinga, Homo ludens, Alianza Editorial, 2012

VVAA, Playgrounds: Reinventar la plaza, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2014

Virginia Navarro Martínez, “Playgrounds del siglo XXI : una reflexión sobre los espacios de juego de la infancia”, Arquitectonics: Mind, Land & Society, n.º 25, December 2013

Paula Ducay e Inés García, podcast Punzadas sonoras, episode Juego, June 2023

*** BASQUE COUNTRY PUBLIC READING NETWORK

CURATOR

María Ptqk

Born in Bilbao in 1976, María Ptqk holds a PhD in artistic research from the University of the Basque Country, a degree in Law and a degree in Economics, a Master of Advanced Studies in International Public Law from Paris II-Sorbonne and in Cultural Law from the Uned-Carlos III in Madrid, and a Master in Cultural Management from the University of Barcelona. Her work is based on the intersections between art, technoscience and feminisms and is a member of the advisory group of the publishing house consonni. She has worked with a number of leading institutions such as Medialab Prado (Madrid), Azkuna Zentroa (Bilbao), Fundación Daniel y Nina Carasso, CCCB (Barcelona), Jeu de Paume (Paris), La Gaité Lyrique (Paris), GenderArtNet (European Cultural Foundation) or LABoral (Gijon), among others. She has curated the exhibitions Soft Power (Amarika Proiektua Project, 2009), A propósito del Chthuluceno y sus especies compañeras (Espace virtuel du Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2017), Reset Mar Menor. Laboratorio de imaginarios para un paisaje en crisis (CCC Valencia, 2020), Ciencia fricción. Vida entre especies compañeras (CCCB Barcelona, 2021 – Finalist of the Asociaciò Catalana de Crítica d’Art Awards & Azkuna Zentroa, Bilbao, 2022), Extinción Remota Detectada (LABoral, Gijon, 2022) and Máquinas de Ingenio (Tabakalera, San Sebastian, 2023) . She is advisor to the Chaire Arts & Sciences (École polytechnique, l’École des Arts Décoratifs – PSL, Fondation Daniel et Nina Carasso) and a member of the ISEA Paris 2023 (International Symposium on Electronic Art) programming committee.